Tobacco Business

The following account comes from a 1976 conversation in which Paul E. Young, Sr., recalled his personal experiences with tobacco production in Miltonsburg from about 1915 to 1925. By that time tobacco farming was essentially a “truck farm” cro

In the early 1800s it was a major (probably the major crop) in the county. In the 1850 census tobacco production in Monroe County was third highest in the state (1,026,866 pounds). In the 1860 and 1870 census Monroe County was first in the state with 3,061705 and 4,368,051 pounds respectively.

Preparing the Land

Trees were cut down to clear land and the tobacco was planted in “new ground.” Often this new land was quite steeply sloped and it was dug up by hand with a mattock-probably because of the roots and rocks. Such steep slopes were usually only harrowed, rather than plowed.

Tobacco plants were raised from seeds in tobacco beds, which were small plots of ground enclosed by wood frames. Brush was burned over the tobacco bed in order to kill weed seeds and the tobacco seeds were sown and covered with cheesecloth. After the plants came up, the ground was prepared as described above, rows were marked out, and the farmers waited for rain. When the rain came the kids in bare feet dropped the young plants in the rows approximately two-and-a-half to three feet apart. Older persons then came by and made holes in row with a peg, stuck the plants in these holes, and squeezed them together.

As the tobacco plants grew they had to be continually cultivated. Watermelons and muskmelons were often planted in the tobacco fields because these plants needed shade which was readily provided by the tobacco plants.

The first step in harvesting the tobacco was to strip (remove) the bottom leaves which were the lowest quality partly because they contained sand and dirt. The next step was to strip the “bottom middle” and then the to

The tops and bottoms were a lower quality, while the best quality came from the middle leaves. The signal for the appropriate time to begin stripping was when the leaves began to turn yellow. The process of stripping left the worker’s hands black and gummy, much the color that results from walnut stains. Unlike the walnut stain, the tobacco stain would wash off.

Processing the Tobacco Leaves

The tobacco leaves were hauled on sleds to the barn where they were strung on sticks using large “darning-type” needles which were sometimes made from umbrella staves. A string was tied to the end of the tobacco stick, which was about four feet long, and the tobacco was strung by putting the needle through the stems and pushing them to the ends of the stick-one to the right, one to the left.

Stringing tobacco leaves was one of the paying jobs a young person could have. Payment varied from one cent per stick on the farm to five cents a stick which tobacco dealer Ed Spangler paid the kids in Miltonsburg. It took about ten minutes to string each stick. This amounted to about thirty cents per hour, which was a very good wage for a young person in the 1920s.

The sticks of tobacco were then hung in the barn or the tobacco house where they were air cured or fired (cured by building a fire in the lower portion of the tobacco house.) tobacco farmers and dealers could tell by the color when the leaves were cured. Sometimes it got too dry and the handlers would have to wait for a damp day, when the leaves were not so brittle, to move the sticks.

When the tobacco was cured, the sticks were pulled out ad the leaves were rolled up into “bulk tobacco,” which was taken to the Packing House on a wagon. At the Packing House, the bulk tobacco was placed on a large square dolly-perhaps an entire wagon load on one dolly- and wheeled to the beam scales where it was weighed. Farmers would “deal” on tobacco the year round, often waiting for the best prices. In Miltonsburg (in the 1920s) Spangler’s would give farmers checks for one dollar each which were good for merchandise in their store. The farmers could earn a bit more this way but they had to “deal out” at Spangler’s.

After it was weighed, the tobacco was taken off the dolly and “bulked.” In this process it was laid in rows with the stems sticking out. The rows were made as big as the bulk one wanted to make and it was built up much like a hay load on a wagon. The tobacco could stay in this bulk for some time, perhaps two or three weeks, until the tiers (tie-ers) could schedule the next step in the process.

When the “tie-ers” were ready they picked up the leaves from the bulk by the armful and carried it to the Tie House. In the Tie House, they laid the tobacco leaves on a long bench which was located along the wall under a continuous band of windows. These windows were necessary to provide ample light to determine the different colors of the leaves during the sorting process.

At this point, the strings, which had been placed in the stems to prepare the leaves for drying, were removed. The sticks had already been removed and kept at the farm. The tobacco was sorted by color and by length of leaf by laying it out on the bench. Some of the highest priced tobacco was known as “yellow spangle” and “red spangle.” The tie-ers would pick out leaves of the same size and select another, especially tough, leaf to fold as a piece of tape, pull through, and tuck in creating a “hand” of tobacco. These hands were taken back to the Packing House where each tie-er made up his or her own pile, or bulk, of their own hands of tobacco and, ant the end of the week, each tie-er’s bulk would be weighed. They were paid about forty to fifty cents per hundred pounds.

Tobacco tie-ing was usually a winter work and a fire was kept in the Tie House to keep the workers warm. It was a very dusty work. The Tie House was always full of tobacco dust, which was collected to sprinkle on cucumber plants to control bugs.

After each tie-er’s bulk was weighed and they were paid, large bulks were made once again by the Packing House employees. The tobacco was stored in this manner until it was “sticked” and suspended at different levels in the Packing House for final curing. Heat would build up in the top of the building and air was controlled by windows on a pivot.

When the tobacco was finally cured, and when it was pliable enough (encased), it was taken off the sticks and put back in bulk. When it was ready for shipment the tobacco, once again, was removed from bulk and sorted for size and color by the packer who, in Paul Young Sr.’s experience, was Adolph Claus (Lots 23, 32&45). The colors considered in sorting were red, grey and yellow.

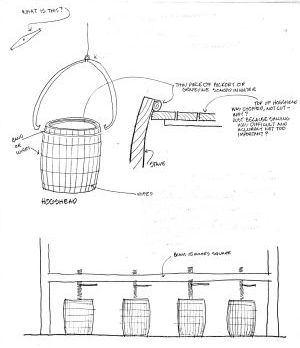

Some of the hogsheads used for shipping the tobacco were made by Philip Menkel (lots 35&36), a furniture maker, and George Landefeld, a carpenter (Lot19); however, Charlie Reller Lot 29), a wagon maker, made most of them. In fact, Charlie, often made the hogsheads ahead of time and stored them until they were needed. Each hogshead was about four feet in diameter and about five feet high. The staves were assembled by being set on a form which was laid out with a large compass. Staves were temporarily held on place by a rope twister until the wires were put on. The large compass was also used to measure the top of the hogshead and lay out the lid on rough “inch” lumber from the saw mill. Boards for the lid were chopped, not sawn.

The sorted tobacco was placed in the hogsheads in essentially the same pattern as that used in bulking. It was then compacted by one of four screw jacks that were anchored to a fifteen-inch square beam in the Packing House. The hogshead was sealed by tacking a hickory sapling or a wild grapevine (that had been soaked in water) around the circumference of the opening to hold the lid in place.

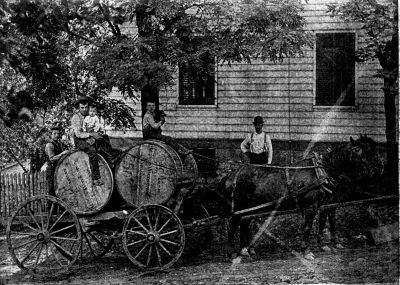

The contents of each hogshead were written on the exterior; sometimes there was more than one kind of tobacco in a single hogshead. They were lifted by a large hook and place on wagons and hauled by teamsters to Woodsfield where the hogsheads, which might weigh five hundred pounds or more, were shipped on the O R&W Railroad to Bellaire or Zanesville and then on to Baltimore. At the auction at Baltimore, they were opened, bid on, and purchased by the major tobacco companies. Top prices were ten cents a pound and bottom prices were one, two, or three cents per pound.

In earlier years the wagons carrying the hogsheads left the village by the north road past the Evangelical Church. Since this was the first leg of the shipment to Baltimore. This road became known as Baltimore Street.

In the early 1900s, the Spanglers bought tobacco through their store; however, they hired Adolph Claus to pack the tobacco for shipping. He was paid (?)? cents per pound for packing. Adolph Claus also packed for John Christman, a tobacco dealer from near Calais, and Ed Peters (Lot 21), a Miltonsburg/Wheeling resident who sometimes grew tobacco on the Cooper Farm which he and his brothers owned at the time. Alex Hardesty, who was the town clerk, also was a tobacco dealer. At one time or another, just about everybody in Miltonsburg and the surrounding area worked in the tobacco business.

The Spangler brothers probably built the Packing House and Tie House after they purchased Yunkes’s store in about 1910. The Packing House was removed by Lawrence Landefeld in the 1950s. The Tie House was remodeled to serve as a garage by Harold Christman and still exists on Lot 16 in 2007.

Oral History Notes

Not all of the Monroe County tobacco was shipped to Baltimore. Richard Riemenschneider, who married Evelyn Young (Lot 11), recalls his father (Sam Riemenschneider) returning to Monroe County from New Albany, Indiana where he worked in and later owned a cigar factory, and hiring people to roll cigars for him near Malaga. In this process the stem of the leaf was carefully cut and removed, permitting a skilled person to roll as many as three cigars from a large leaf. Sam Riemenschneider had boxes holding twelve cigars made and he sold them to local stores. No doubt others practiced the same business.